Here is an object (for lack of a better name, let’s call it that for the time being) discreetly located at the crossroads of several of Bertrand Lavier’s “building sites”. But this is already going too fast: one does not enter like that into the work of this artist, although it is apparently so easily accessible, and one must remember how much and how it is built in a singular way...

Here is an object (for lack of a better name, let’s call it that for the time being) discreetly located at the crossroads of several of Bertrand Lavier’s “building sites”. But this is already going too fast: one does not enter like that into the work of this artist, although it is apparently so easily accessible, and one must remember how much and how it is built in a singular way. One of its singularities is that it prefers redistribution to distribution, which is not self-evident in a field in which gluttony has become the main feature. To distribute: to constantly produce something new, if possible new, and to spread it wherever there is a demand. Redistribute: slowing down production, reorganising things already in place at its own pace, otherwise, without necessarily responding to demand but questioning supply. And this work, which is said to be marked out with objects (Marcel is passively summoned to all the ends of the field that Lavier surveys) is above all traversed by time, and the modelled propositions of its redistribution. Lavier is among those who consider with equal seriousness and excitement the exercise of producing a new work or reorganising his old works, as we will see at the Musée d’Art moderne de la ville de Paris in June 2002. Basically the curator of his own exhibitions (like, after all, the few great artists of our time), he has chosen to develop and pursue various “building sites” and explains: “I don’t have a blue period followed by a pink period. An artist can go down one path and then have other ideas. He has two choices: close the door to his first idea and work on another idea, or keep the door open and consider the freedom to continue exploring his old ideas [1], he told Jacques Henric in 1991.

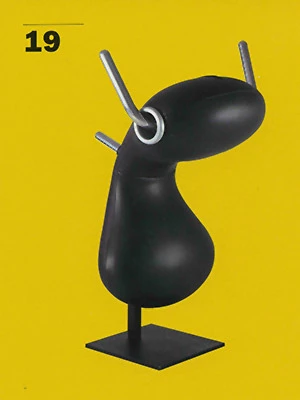

One of his famous “building sites” (but aren’t they all, of course?), which is usually referred to as “objets soclés”, led him to entrust Mr Halal Rachedi, a craftsman specialising in the presentation of objets d’art premier, objects which, although they are obviously not art premier, will nevertheless be treated with equal respect. To fold time back on itself, as has been said, is an obstinacy, which led him to constantly reorganize what was done to give it another contemporaneity, which led him to replace in a bar in Avignon the antique objects which served as decoration for contemporary everyday objects, etc. The “construction site” of socalled objects, a vast undertaking to destabilise the norms of good taste and bourgeois strategies for asserting distinction, meets here in a peripheral way with other construction sites. First of all, that of “grafts”, whose principle rests on the addition of two objects to form a third: a refrigerator on a safe, Varèse’s music on a sculpture by Calder, or the subtle N°5/Shalimar (1987), a simultaneous diffusion of the two famous fragrances, a project for which Lavier often called upon elements of contemporary design. A table from Prouvé on a freezer, a Panton Chair (1959) on a refrigerator, or more recently the same Panton chair adorned with the orifice of the Eames’ Conversation Chair (1948), and the seat of a Bertoia chair on the base of the Eames’ rocking chair. Then there is the Walt Disney Production chair, built from a 1947 Walt Disney comic strip that shows Minnie and Mickey at the Museum of Modern Art. Bertrand Lavier has exhibited remakes of works drawn by Disney, photographed or interpreted in volume and then redistributed on a real scale in existing spaces or themselves reconstituted from the original comic strip. The Embryo chair has all the characteristics of the Disney line: the colour and roundness of the ears of the prolific mouse as much as the look of the sculptures imagined by the designer.

In more than one way, it overlaps with Bertrand Lavier’s world. Embryo (embryo), a chair designed by Marc Newson in 1988, was originally conceived to be covered with a material whose use, for a seat, is more akin to the principle of grafting. As an Australian, Newson chose to cover this chair with the fabric from which surf suits are made ‘ later on, he would use the very shape of surfing for a deckchair. This impertinent gesture is probably also due to the non-conformity of his professional education: Newson did not study design, but jewellery and sculpture. And need we remind you that Bertrand Lavier did not study the art of art but that of landscape, at the Versailles Landscape School? Newson became familiar with design by reading specialist magazines, Lavier passing by the window of an art gallery next to where he lived every day: each one developed his skills outside the teaching of a master whose practice he would have feared they would have reproduced. When he was born in 1963, Newson had been preceded for almost fifteen years by Walt Disney’s images showing Mickey at the Museum of Modern Art: a temporal short-circuit that probably did not displease Bertrand Lavier, who nowadays entrusts Mr Halal Rachedi with Marc Newson’s impertinent chair, zipped from the back like a diving suit, sitting snugly on his tubular metal legs, so that he can find the most suitable way of presenting it. At the same time, Embryo becomes an object of both the present and the past, in a telescoping of memory and the gaze – a status that, like other Newson chairs, auction houses will not fail to confirm quickly, as they did for his 1985 Lockheed Lounge, a hallucinating object built like an aeroplane wing, which recently broke records in New York. By sacralizing a design object in this way, Lavier gently reproduces the exhilarating movement that records production and registers it in the inventory of the exceptional objects of our time, barely ‘and invites us, as usual, to rethink our value system. He also invites us to consider an armchair as an object of art, and we can bet that it is not only the fifteen years that separate us from its birth that invite us to do so.

In the end, this object, which is not more relational than interactive and yet so obvious, composed of another object that has lost its functionality and of a gesture that is essentially discreet, offers itself to us as the fixed expression, a little like Bernini’s Saint Theresa, of a great inner turmoil. As well as the photography of an era that we would not have known how to live through, and its broadcast on television one evening, just a few years later.