Six Constructions: An imagined dialogue.

To displace the gaze, to displace questions.

Such simple and unpretentious directives—to look, to ask—are the basis of a rigorous, pragmatic initiative. To look, to ask questions, these are the primary cognitive impulses that allow one to cut through a field of endeavor (both object and conceptual production) that is clouded by inflationary discourse, self-consumption, and promiscuous references…

Design is cannibalistic...

Six Constructions: An imagined dialogue.

To displace the gaze, to displace questions.

Such simple and unpretentious directives—to look, to ask—are the basis of a rigorous, pragmatic initiative. To look, to ask questions, these are the primary cognitive impulses that allow one to cut through a field of endeavor (both object and conceptual production) that is clouded by inflationary discourse, self-consumption, and promiscuous references…

Design is cannibalistic. Design feeds off itself.

In the large field of visual culture, no single discipline (high or low; traditional or new; functional or purely aesthetic) has retained a sense of autonomy. Visual artists have cannibalized design to the point that the very notion of use-value can no longer be used distinguish an “artistic” project from a “design” project. The post-utopian community and furniture objects of Atelier van Lieshout, Jorge Pardo’s house that is also his artistic opus in Los Angeles, the functioning “Donald Judd bar” built by Tobias Reyberger for the Munster Skulptur Projeket…these are all salient examples of visual artists blurring the boundaries. Of the desire of visual art to not only cannibalize its own history but also neighboring disciplines. Just like design.

Is it reactionary or forward thinking to think about the specificity of a discipline, to ask questions about the status of visual and object production today? Is it possible to reconsider the fundamental issues that have been eclipsed by this process of disciplinary boundary blurring? In order to reevaluate issues such as use-value, one must also ask use for whom?

Designer’s “objects” are alienated because of their condition of being “design objects”, image objects, fashion objects…

Like visual art, this loss of disciplinary-specificity coupled with its own cannibalism has allowed “design” to take on ambiguous uses. How many times have curators (of art, fashion, marketing—the notion of the curator has now become an important figure in the culture at large) used design to for ends that mismatched the original intention of the object? Is design a field of object production that is at the service of others? Can design be a critical, self-sufficient form?

The furniture-object is not self-sufficient.

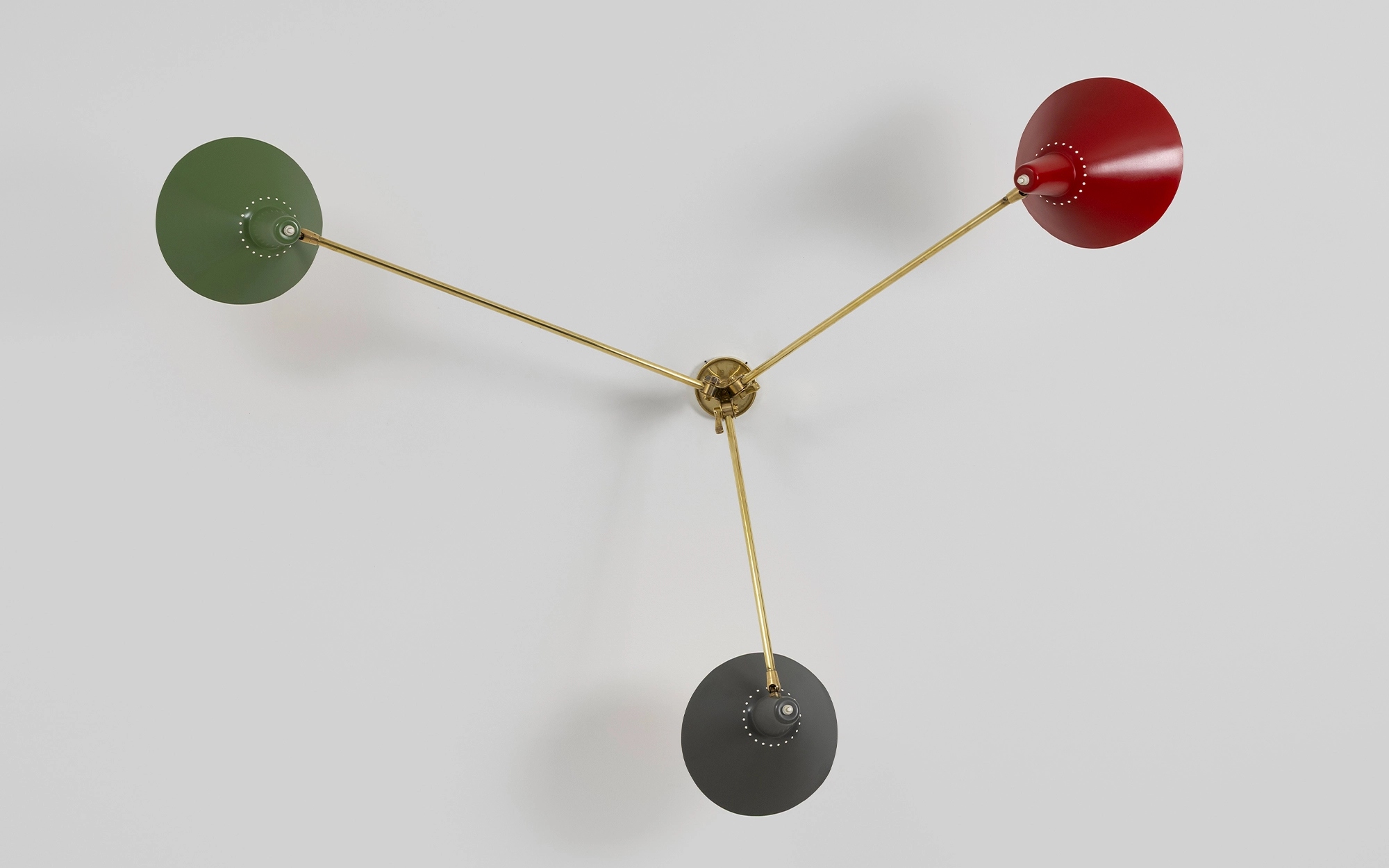

Why make a flat plane? Why sit down? Where to sit? What is a table? An armoire? A light fixture? What symbolic or exchange value can these objects presume to hold?

To attempt to answer to these questions about the foundation of these “furniture-objects” requires taking into account the cultural and material environments in the present tense. To do the opposite would be outdated, passé.

The cultural and material context today is riddled with not only this general sense of confusion (whether deliberate in terms of an ideological agenda—is all this cannibalism the leftovers from a postmodern leveling of high/low, functional/aesthetic?) but also a lack of retrospective analysis. It is all too easy to ride the current flow and exchange of images, of fashion, of cultural status quo.

Is it possible to create a cultural practice that is neatly inscribed between the impossibility of the avant-garde (naiveté of new forms) and of passive acceptance? What would be the starting point of such a practice? Not only to return to elementary questions and essential functions of everyday life, but to take a risks in regards to reception, use, and value.

An objective: to break the alignment with “furniture making” (le mobilier) and its history. To instead revive the link with our primal necessities as physical and mental beings. These constructions are supports. Supports for our bodies and for our objects.

Tabula rasa is almost impossible in any field of production. But it might be necessary to suspend the charged weight of history and the self-referentiality of a discipline to get to the basics, to engage in a serious reexamination of one’s practice.

The materials used for these constructions are not specifically concerned with the domestic sphere.

These constructions are not pre-destined for a specific milieu. They are no where, and therefore everywhere. Their real scale and dimensions are made in reference to the human body. A human whose first need is to be isolated, to be raised from the floor.

Can furniture be considered as a pedestal?

Something that looks like a lounge chair—a flat surface on an incline that is scaled to a prostrate human body—yet whose angle of incline are unexpected and offers an open, trapezoidal space underneath it.

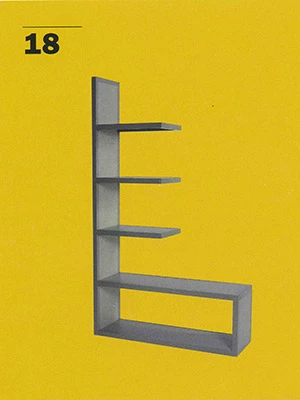

An object that at first glance recalls a bookshelf in its stature but that seems unnaturally truncated. Where is the vertical element meant to hold the books in place? Is it okay to sit on the rectangular base that lifts the construction off the floor?

A table that seems to be pared down to an essential line, a simple volume—two verticals and a horizontal plane—but that has an awkward horizonal “foot” that continues horizontally at its base, on only one side. Does it need this strange appendage to hold itself up? Or is this an aesthetic choice—at taste for asymmetry?

If photographed outside of all architectural context, they have no sense of scale.

Where do these materials come from? Metal support structures and fiberglass panels that do not carry the heavy symbolic weight of their industrial origins. The pleasant color and luminous quality of these constructions counterbalance their perplexing nature—these are analytical objects, they pose questions, but they are visually neutral. These six constructions seem to come out of a laboratory than a designer’s studio.

And if these “furniture-objects” lost a little of their presence to become nothing but diagrams, ledges, supports, necessary extensions of our bodies?

Underneath these open-ended objects are recognizable forms—there is no tabula rasa. By keeping a whisper of the familiar (a table, a chair, a desk, a bookshelf), Szekely is able to create objects that retain use-value (these constructions are not a hybrid furniture-sculpture) that is not completely codified. They generate a gentle sense of ambiguity because of this subtle play of asymmetry in terms of both form and use. Szekely confronts us with deceptively simple questions—is it okay to sit here, is it okay to use this in this way? Szekely doesn’t give us an answer—his constructions always retain the form of a question. The person who is standing in front of these objects must decide for himself or herself if it is okay to use these objects in the manner they choose. The only answer is intuition.

This exhibition “Six Constructions” is not an answer, but just a question.

More than just questioning the history of furniture, Szekely humbly but effectively challenges the routine behaviors, social conventions, and cultural contexts that have formed this history.

_

Martin Szekely, December 2001

Alison M. Gingeras, March 2002